The Centennial Case Is A Good Piece Of Shinhonkaku Mystery Propaganda

22 12月 2024

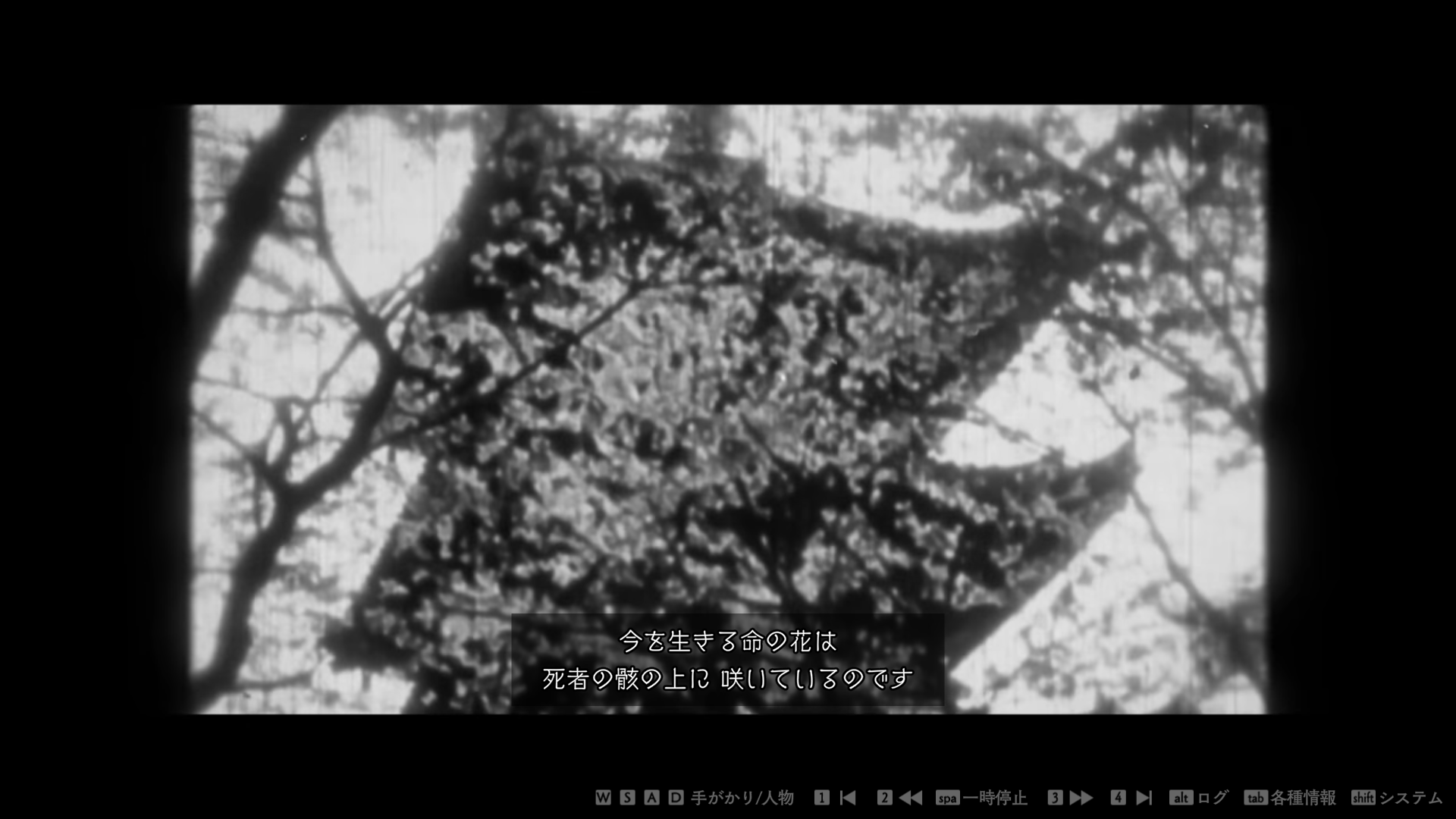

The Centennial Case: A Shijima Story begins with a perennial cliché: there is a dead body buried under a blooming sakura tree.

In Kajii Motojirou's iconic horror short story "Under the Cherry Trees", the narrator claims that the vitality of these beautiful trees comes from their roots sucking the energy out of corpses:

What makes those petals? What makes those pistils? I can almost see the silent ascent of crystal liquid coursing dreamily through those veins. (trans. David Boyd)

For the narrator, the beautiful but vague images of the ravine do not excite them. It is the carnage they thirst for. They don't know how they got the idea, but it's one they can't easily let go of.

And the Japanese literary imagination hasn't abandoned this striking image either. One example will suffice: Beautiful Bones: Sakurako's Investigation is a series of detective novels adapted into an anime, whose Japanese title is 櫻子さんの足下には死体が埋まっている (Sakurako-san no Ashimoto ni wa Shitai ga Umatteiru, lit. Corpses are Buried under Sakurako's Feet). For better or worse, the invocation of the macabre and the beautiful is more or less a meme in the mystery genre.

But for The Centennial Case, this is but one of many references scattered throughout this FMV mystery game. The wellspring of history that the game draws from is much like the corpses found under the sakura trees: rich in detail and also a bloody mess.

Kagami Haruka is a bestselling mystery novelist who becomes involved in the dramatic case surrounding the history of the Shijima family. Her medical research colleague, Shijima Eiji, is interested in a so-called Fruit of Youth that the family had, but he has been unable to pry the truth out of his father. Meanwhile, the bones buried under the sakura tree have caused a media frenzy and are an unfortunately effective reminder that the family has not overcome its miserable history of death and suffering.

To make the situation even more complicated, Haruka and her editor Yamase Akira have also stumbled upon a serialized mystery story written by an ancestor of the Shijima family. It is published in the same magazine as the horror-mystery writer Edogawa Ranpo. The game really starts with the first chapter when Haruka reads the stories and enters the Taisho era as Shijima Yoshino, an inquisitive girl who wants to participate in a private auction to get the Fruit of Youth that was stolen from her.

While the overarching (and most important) case takes place in the present day, many of the cases in the game are framed as short stories found in literary magazines and manuscripts. The main actors who appear in these historical segments usually play characters who have already appeared in the present; the explanation is that these old books are difficult for Haruka to read, and she needs a way to anchor the narrative with people she's already met. This allows for some fun social commentary: not only do the characters dress in period costumes and walk around authentic locations, but the way they talk and think about things like gender is grounded in history. We can trace a continuity of ideas and see how people behave differently over the years. It also helps raise the stakes of the mystery: How does any of this relate to the present? The scope of the mysteries turns out to be bigger than I expected.

The historical mysteries are also excellently plotted and well dated to their respective time periods. When the detective character decides to present her case, there are no surprises withheld like the infamous coroner's reports in the Ace Attorney series. The cases are immediately solvable. I find fair play shockingly rare in mystery video games, so I was pleased to have enough information to theorize how a murder happened and how the perpetrator got away with it with all the information I had.

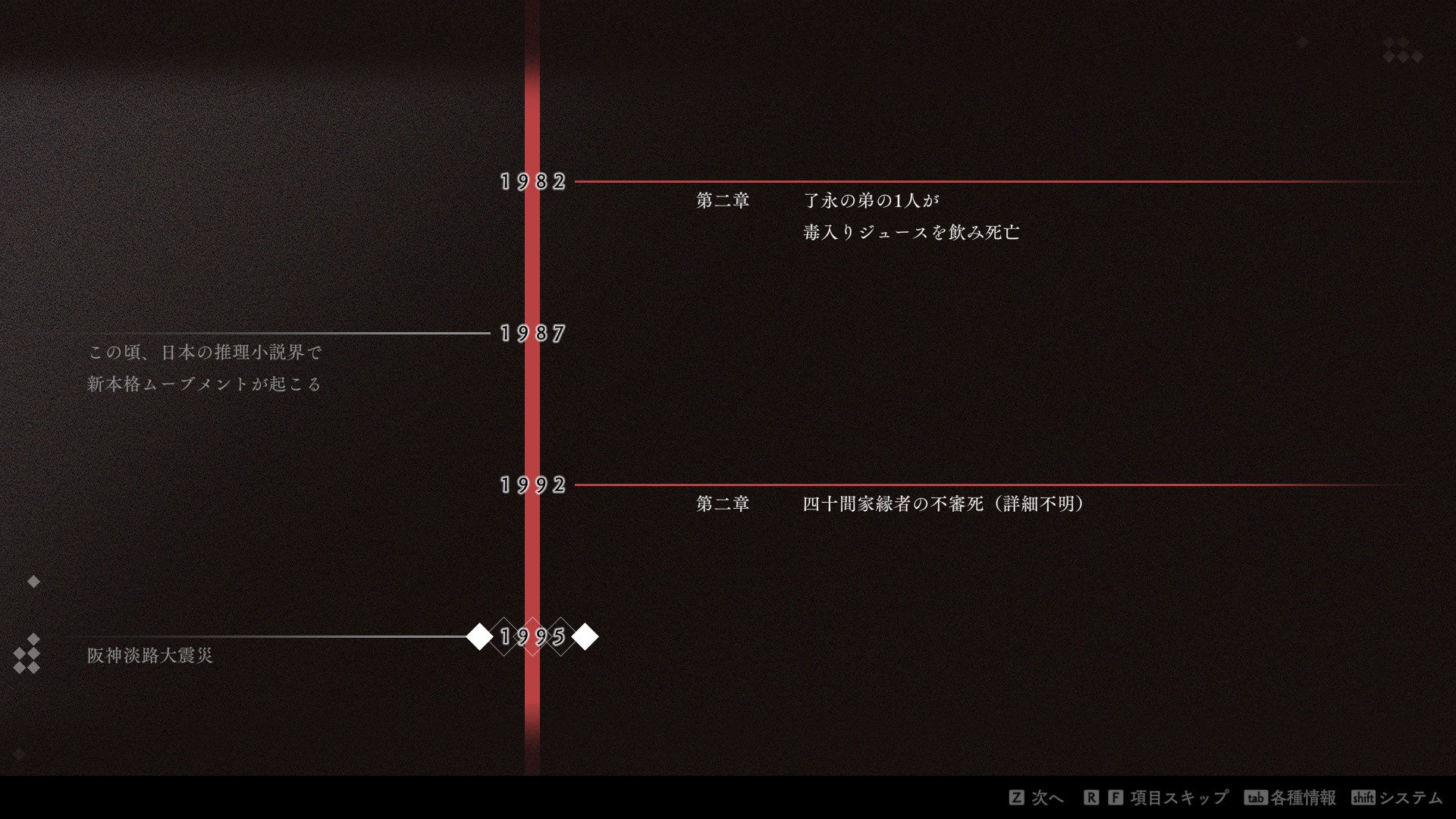

And after completing each case, the player is booted to a historical timeline of events from the game and the real world. In addition to major events in Japanese history like the Kanto Earthquake and world history such like 9/11, the timeline also includes the debuts of major mystery writers such as Agatha Christie and Matsumoto Seichi.

Funnily enough, the timeline also includes the beginning of the Shinhonkaku (New Traditional) Mystery movement as a key event. I'm a fan of this movement because it recognizes that the mystery genre is very contrived, but still finds some value in it. However, its solutions are polarizing for many readers: books can comment directly on the genre and characters, and they can also include unreasonable conclusions to provoke readers. Not everyone can be a shinhonkaku fan, and that's fine.

But what I admire about the genre is how much more food for thought it provides after the mysteries are solved. While it will always suck to be spoiled by a mystery, I find that the themes they explore stay with me more than the thrill ride traditional mysteries like to provide. The ethics of detective work, the ruminations on collective trauma, and the ambiguity of absolute truths are more memorable than a well-constructed box of puzzles that characterize traditional Agatha Christie mysteries.

And The Centennial Case avoids the ostentatious excess of the genre by keeping most of the social commentary and metafiction in the realm of subtext. If one takes the trouble to dig through the game's themes, especially in the epilogue chapter, there's a lot of interesting things the game says about what it means to be chained to history and to break free of it.

It's unfortunate that the game is riddled with the most tedious gameplay imaginable. While I'm mostly neutral when it comes to watching the movie play out and occasionally pressing keys to take note of a clue, the segment that grinds my gears is how you piece together the clues and puzzles.

The way The Centennial Case implements deduction is, to put it bluntly, terrible. Each case is full of questions posed to the player (When did the person die? Where were they killed?), and the player must select clue tiles that appear throughout the FMV segments. The player must drag clue tiles onto a long line of question tiles, and correctly placed tiles create hypotheses (some true, most blatantly false). Question tiles can also have multiple answers. Fortunately, all tiles have shapes that connect to each other, so the player doesn't always have to guess.

But there are two major problems with its implementation:

The controls are terrible. When a friend asked if the game was playable on Steam Deck, I noted that it should be fine because any control scheme feels godawful. I was using keyboard and mouse, which should be the best way to play the game. But dragging tiles over and over made me quickly sick of the gameplay, and the later cases have much longer sequences. I've heard from a friend who played it on console that the mouse cursor also scrolled slowly.

Many clue tiles also feel vague because they are utterances of suspects. To give a hypothetical example, imagine that the game asked you how a vase at the crime scene got smashed: you have to find utterances related to it (the vase shard is over there!). I wanted to see every possible false hypothesis in the game in case the puzzle used an element I wasn't expecting, which is why the way the tiles are categorized under FMV clips is so unhelpful. I hated trying to associate what an utterance is with a line in a long video clip.

Everything else about the game is fantastic. The performances are excellent and hammy when appropriate, the music is very listenable and suspenseful, and the puzzles are super engaging.

But I just find the gameplay too awful to give it an easy recommendation, because you spend at least fifteen minutes on each case.

It sucks so much.

Nevertheless, I still want people to play this game. I think it says something about how we should appreciate how historical conditions shape us.

While I find the English title apt for its scale, the Japanese title, 春ゆきてレトロチカ, describes the game's aesthetic: the passing of spring fashioned in retro-chic clothing. New beginnings emerge after things have come to an end, just in fashion lingo. This sounds a lot like the Orientalist cliché, mono no aware, where "expert" commentators note how the noble Japanese are perceptive enough to feel a pathos about how things must inevitably change, the transience of everything, and all that nonsense.

But what I find most compelling about this game is how it roots this cliché in a history full of violence and dreams. The optimism of Taisho Democracy potentially giving women rights isn't some utopian dream; it seemed possible until the Kanto Earthquake and World War II interrupted women's suffrage. No one feels emotion from change itself; it's because change is so destructive and creative that trauma follows. Today's Japan is still marked by the legacies and broken promises of the Taisho and Showa eras.

We get our traditions and our life from the corpses buried under our feet. The epilogue of the game wants us to face this truth. What we do with it is another matter, but I think it's a lesson worth learning.

I really like The Centennial Case. It was made by people who obviously love shinhonkaku mysteries and have experience in making adventure games. The game can work very well as an introduction to Japanese mysteries, if not for the atrocious gameplay.

If any of this makes you want to play the game, please do. And if you want to read more shinhonkaku mysteries afterwards, then I think the game has done its job in teaching its players that mysteries are a fascinating genre that will always comment on what needs to be done in the microcosm of a mansion.